Eliciting Latent Knowledge

18 Aug 2022My friends Uzay Girit, Pranav Gade and I recently participated in an ELK (Eliciting Latent Knowledge) contest held by Prometheus Science with a prize pool of $100,000. Our Predicting The Predictor proposal won 2nd place.

Suppose we train a model to predict what the future will look like according to cameras and other sensors. We then use planning algorithms to find a sequence of actions that lead to predicted futures that look good to us.

But some action sequences could tamper with the cameras so they show happy humans regardless of what’s really happening. More generally, some futures look great on camera but are actually catastrophically bad.

In these cases, the prediction model “knows” facts (like “the camera was tampered with”) that are not visible on camera but would change our evaluation of the predicted future if we learned them. How can we train this model to report its latent knowledge of off-screen events?

Contrary to Neural Network interpretability/transparency focused on low-level neurons or circuits, ELK focuses on generating natural language descriptions that reflect the model’s “true beliefs”. In short, this AI-alignment problem is trying to think of ways to get an AI to tell the truth in a contrived hypothetical situation. Here are our two proposals:

Predicting the Predictor

In this 1st proposal, we add layers to our reporter so that on top of relaying latent knowledge, it can predict the predictor’s output given part of the predictor’s state.

The idea here is similar to the one in the strategy “penalize depending on ‘downstream’ variables”. We want our model to understand the general reasoning of the predictor, and not predict based on a human simulator model that looks at the output.

We can feed our reporter model part of the predictor’s state/activations on given inputs and encourage its ability to use this information to predict further activations and even predict the final output of the model. This incentivizes models that have learned the reasoning of the predictor, which is necessary to build a direct translator. Another strategy that builds on this is to allow the reporter to do the following:

- on a given data sample, let the input of sequence actions to the predictor be

X - feed the reporter the sequence of actions

X, the predictionY, and the predictor’s state - define a set of transformations on

Xthat modify the original sequence of actions - make the reporter predict the new output of the predictor off of the old predictor’s state, taking into consideration the transformation of the input sequence

- compare to the actual predictor’s predictions on this data and include the average distance in the loss

This method has similarities to the one proposed in “Strategy: use the reporter to define causal interventions on the predictor”, by defining causal interventions on the input sequence itself rather than the predictor state.

This strategy is similar to the previous one except it also allows us to increase the training data set for our reporter and make it more robust. Note however that the way you define your transformations is important: you could remove part of the sequence or describe classes of changes instantiated by a helper AI. It also doesn’t require splitting the predictor state arbitrarily to see how the reporter reacts, fixing the problem with the downstream variables strategy.

In both cases, these approaches encourage models that have a conceptual understanding of the predictor they must elicit latent knowledge from.

Counterexample: malicious reporting

Note that this strategy does not directly train the reporter on relaying truthful latent knowledge but encourages it to understand that latent knowledge and to lean towards an understanding of the predictor rather than being a human simulator. Indeed, it does not incentivize accurate retelling of information but incentivizes models that at least absorb information instead of simply being a human simulator. By including a loss term on reporter’s predictions and their distance to actual predictor outputs, we are not punishing malicious reporters that would attempt to lie about the elicited latent knowledge, and this is one of the main limits of this proposal.

Token AI

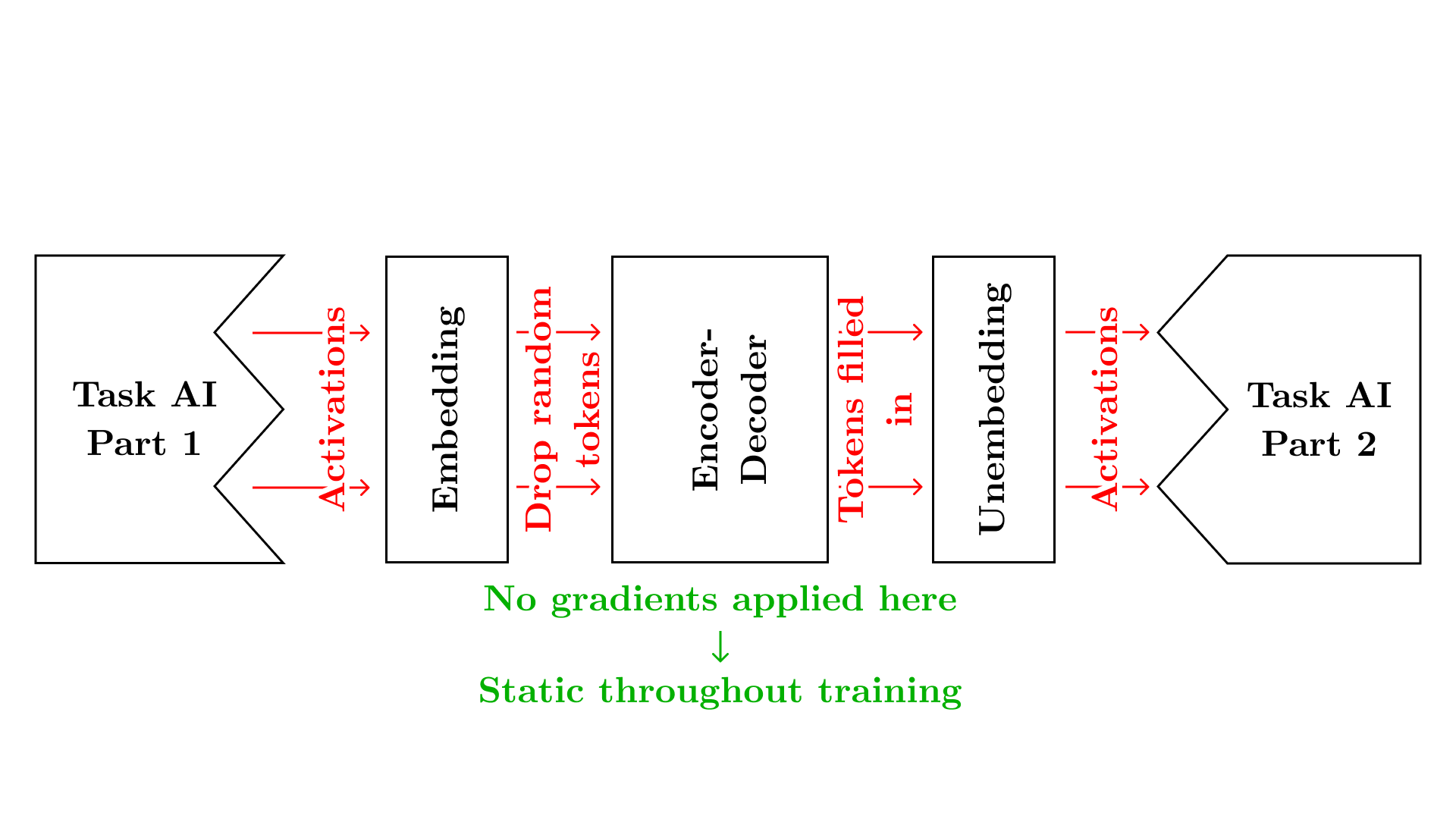

Our 2nd proposal is to have the activations at some layer (potentially all layers) go through an embedding layer and be passed to an encoder-decoder model like BERT. At this point, we’ll drop random tokens from the sequence, which will have to be reconstructed by the encoder-decoder. This has two advantages: we can add “how sensible the natural language sentence is” to the loss term. And since this would incentivize steganography, dropping random tokens will ensure that probabilistically, there is an arbitrarily low chance (which we get to choose to be as low as we desire) of the steganography/encryption scheme working.

An information-theoretic bound here compared to a model where we don’t do this can allow us to push the chance down to 0. That is, if we figure out the minimum amount of bits needed, we can drop all extra information. If this ends up not producing sentences simple enough for a human to understand, we can add a human in the loop whose job is to read the sentences, understand them, and rewrite them in human’s own words.

An information-theoretic bound here compared to a model where we don’t do this can allow us to push the chance down to 0. That is, if we figure out the minimum amount of bits needed, we can drop all extra information. If this ends up not producing sentences simple enough for a human to understand, we can add a human in the loop whose job is to read the sentences, understand them, and rewrite them in human’s own words.

We expect this to work because BERT is trained on completing English sentences, so the input sentences will have to make sense. Dropping information will make steganography/cryptography pretty difficult, and encourage duplicating information. Having a human in the loop will ensure that everything is represented in terms of human-level concepts, or teach the human the concepts from first principles.